Policy Punchline is a podcast, created, produced, and edited by a group of very talented Princeton University students – led by Tiger Gao, The podcast promotes long-form dialogues on frontier ideas and urgent issues with scholars, policy makers, business executives, journalists, and entrepreneurs.

Policy Punchline with Martin Fleming

The following is the portion of the Policy Punchline podcast on the post-pandemic era.

“My punchline is that we’re very likely to see very dramatic policy change and transformation over the course of the next several years….That’s part of what we’re seeing in the streets today…. [T]he people are singing in the streets, and there is now enormous pressure for change. What we’re seeing in America this summer might be akin to the French revolution.”

Martin Fleming was formerly the IBM’s Chief Economist and the head of IBM’s Chief Analytics Office. His research focuses on artificial intelligence, the future of work, and digital currencies.

Q: You’ve written a lot about the future of work and how it will be impacted by AI. The Covid-19 crisis has somewhat caught us off guard, forcing many workers to transition to working from home. Has Covid-19 disrupted any of the trends that you were previously predicting?

A: It really has created an enormous opportunity for transformation. Working from home is one example, but if you think a bit more broadly, consumers are looking to make decisions in a fundamentally different fashion.

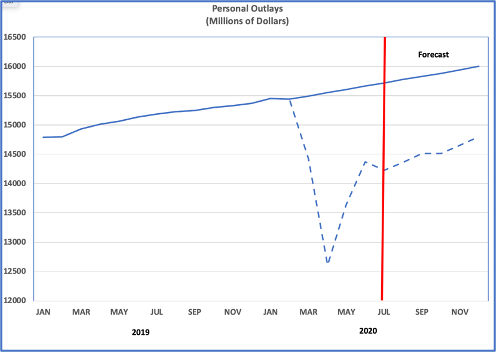

There has been a lot of fear and anxiety about the spread of the virus. One piece of data to help to bring home the point is that in the month of April in the U.S., 33% of all the income earned was saved. This reflects fear and incredible caution. The savings rate is usually in the order of 6%. We’ve already seen the attitudes of consumers shift quite significantly, and it’s going to take time for all of that to unwind itself.

Ask yourself the question, are you seeing folks attending large events, sporting events, or theaters? I think the answer is no. College students are the exception, as they are still gathering in large crowds, but that’s not happening with most of the rest of the world. All this to say, consumer purchasing has been dramatically impacted by all of this, and it is going to take time for that to unwind.

Q: On the topic of the future of work, we saw that the Fed released a report that said the unemployment rate at the end of the year was expected to be 9.3%, which is a huge number we haven’t seen in a very, very long time. And you had released your own work on the future of work in 2019 when Chairman Powell was commenting on the first tight labor market the U.S. had seen in years. So, now with this sudden transition, what would your thoughts be on how the next few years might shape out?

A: We are going to see the global economy struggle over the next few years. You have to first begin by having a view about public health conditions and you also have to separate public health from healthcare. Healthcare would be care delivered in a physician’s office or hospital setting which of course matters in this case because the capacity of the system to deliver care is the constraint that policy makers face in the presence of Covid-19. Public health is around epidemiology and virology and understanding the virus and the spread of the virus and where that might be headed into the future.

Our view is that it going to take time for the global population to develop sufficient immunity for the virus for no longer to be a threat. The virus will never completely go away like many other viruses we have seen before. So, we can hope over the next three or four years there will be sufficient immunity, probably as the result of a vaccine, that will mean that the virus will no longer impact our lives on a daily basis.

So, the question is how are we going to reach that immunity and how long will it take? It’s probably not going to be herd immunity and we are probably going to have to get a vaccine to be distributed worldwide. Billions of people will have to be vaccinated to build up that immunity and that will take time. Having a vaccine developed in 12-18 months would be a record pace, and even then, the vaccine would have to be manufactured in large quantities and deployed through the healthcare system.

The reason why I take you through all that is because it impacts the economic outlook. We recently got a forecast that was published by OECD, which is expecting a recession in the second half of 2020 and the beginning of 2021. This would be caused partly by the continuing of waves of infections. Workers are fearful to return to work and consumers are fearful to leave their homes. This effects the supply and demand of the labor market and we can see its driven by the public health outlook.

Q: Do you foresee the COVID-19 pandemic leaving long-lasting impacts on the economy?

A: Economic shocks have, unsurprisingly, a significant impact on global economic activity. I’m sure many of your listeners will have learned about the great financial crisis of 2008 and realize that in the subsequent 10 years since that time, the global economy, and in particular the U.S., has really been quite disappointing in terms of productivity growth, wealth accumulation, and increased income inequality.

It turns out that economic shocks of the magnitude of the great financial crisis quite often have these persistent effects where disappointing or subpar growth conditions exist for an extended period. We can look, for example, way back in history to the 1970s, when there were two very large oil price shocks, both of which were followed by recessions and then both of which subsequently were followed by very weak economic growth.

You are probably familiar with the “China shock.” David Autor at M.I.T. has done a lot of work with his colleagues on the impact that the entrance of China into the global economy and its emergence as the world’s factory has had on many parts of the United States. Not only have we seen job losses, but we’ve seen quite dire social consequences, like opioid addiction, increased incarceration rates, suicides, and divorces. It is an economic shock that has had quite deep and profound social consequences.

However, not all economic shocks result in such pessimistic or poor outcomes. If you think about what happened during the Second World War in the United States, industry and manufacturing converted on a massive scale to wartime production. The auto industry was producing military vehicles. There were clothing manufacturers who were producing uniforms and equipment. Even an organization like IBM converted production to produce weapons that were needed by the military. There was enormous disruption to economic activity.

There was a large military that was built. Many young men joined the military, learned new skills, learned new behaviors, new ways of living, became much more disciplined in their lifestyles. And, of course, many women who weren’t in the military, went out to work because the men who left had to be replaced by the women who stayed home. When all of this came to an end, with all this skill that was built up through the experience in the military, through the experience in the workforce, and the benefit of the GI Bill, there was an enormous increase in the education level of the workforce. The transformation of the manufacturing sector and all the skill that was built up resulted in a period of very strong economic growth.

The key is when economic activity was disrupted, businesses did no return to their old ways. They found new ways with new technologies, new manufacturing processes, and new facilities combined with the new skills that workers had acquired. The resultant transformation contributed to a 30 year period of very strong growth.

Of course, there was also the Cold War, during which the enormous investment in the space program and in the military created considerable intellectual property and intellectual capital, which also added to growth. One quick example that I find quite interesting is that one of the reasons why cell phones work so well today is because of data compression. There were enormous advances in data compression in the space program in the 60s and the 70s because data was being transmitted over such vast distances in outer space. Data compression became very important and has now led to enormous innovation that we are still continuing to realize all of these years later.

So, that’s an example of a shock – a military, World War shock – that then led to enormous, enormous growth. We can debate the causality, but it’s quite an interesting coincidence as to how all of this happened, with industry transforming from the old way to the new way, new skills, new technology, and new intellectual property being developed.

My question is, “is the pandemic a shock of equal magnitude?” And if we’re going to go through this for three or four years and we’re going to disrupt our lives and be forced to find new ways to do things, is that going to result in some very positive outcomes in terms of growth, productivity, income growth, wealth, and perhaps even more or less unequal distribution of income? Those are some of the questions that we have begun to think about.

Q: Returning to what you mentioned earlier about the magnitude of the current pandemic crisis, have any other economists mentioned any opinions that are contradictory to yours on what they think about this crisis?

A: I haven’t heard any yet, but I think it’s only because it’s too soon. We’ll have as many opinions as we have economists on this topic, I’m sure, before too long. However, when we talk with C-level executives who are leading large organizations, they’re really focused on two real priorities.

The first priority in all of these discussions is the health and safety of their workers and their workers’ families. For all the criticism that business leaders and the business sector get, it has really been quite heartening to see the real genuine concern that business leaders have over the health and safety of their workforces.

The second is the notion of this longer-term transformation. I would say that most leaders don’t have a firm or clear view as to where that transformation is headed or what it might look like. But, intuitively, they believe that the kind of disruption that we’re experiencing is going to result in significant change over a period of a few years. It’s still a bit nascent, but nonetheless, there’s a recognition that we’re in for some fairly significant change.

Q: Is there anything else that is going on in your mind that you think we haven’t touched on? Anything interesting that you think might be good for our listeners to know?

A: I think the topic of interest for me at the moment is the topic that we’ve spent time on: what is it that will follow the pandemic? The virus is not going away. We, as humans, develop immunity to them. The question is, how long is it going to take to develop enough immunity that we can return to a life where we don’t have to be concerned with social distancing and wearing masks. That day will come, but it’s going to take time. And when that day arrives, what will the world begin to look like? What will the transformation begin to be? Will it be more of the same or will we see some fundamental differences?

Q: Since the name of our show is Policy Punchline, we have to ask: what’s your punchline here for the show?

A: My punchline is that we’re very likely to see very dramatic policy change and transformation over the course of the next several years. In the U.S., it is more likely to occur under a Biden administration, perhaps less likely to occur under a second Trump administration.

That’s part of what we’re seeing in the streets today. There are riots, protests, and a reaction to the racism and bigotry that we see. But I think a lot of the reaction that we see in the streets is also reflective of much greater pressure in terms of not only the pandemic, but the disappointing economic performance in general.

From Les Misérables, there’s this the famous song “do you hear the people sing?” Well, the people are singing in the streets, and there is now enormous pressure for change. What we’re seeing in America this summer might be akin to the French revolution. That is where the policy punchline comes. What are the changes that we’re going to see in policy as a result of all of this pressure that has built up, not just, importantly, in the racial sphere, but also for workers and from a labor market perspective, as well as campaign finance and the role of money in government? I think that we’re going to see some quite significant change.

There probably will not be any presidential candidates promising the voters of America radical change, because that’s probably not a good way to get elected president. But ultimately, I think that’s what’s likely to emerge, and it’s in part a reflection of what we’re seeing in the streets today.